A. Introduction – An Overview of the TCJA of 2017

On December 20, 2017, the U.S House of Representatives and. Senate passed H.R. 1, “[a]n Act to provide for reconciliation pursuant to titles II and V of the concurrent resolution on the budget for fiscal year 2018” (referred to hereinafter as the “Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017” or (“the TCJA”)), enacting the most sweeping tax reform bill in 30 years. Then-President Trump signed the TCJA into law on December 22, 2017. And as a result, most of the provisions of the TCJA became effective for tax years beginning after December 31, 2017 (January 1, 2018), and ending on December 31, 2025.

However, America now has a new president, Joe Biden, who during his campaign and subsequently after taking office has promised to bring an end to what he characterizes as the sweeping tax cuts in favor of corporations and high net worth individuals at the expense of the working-class Americans that the TCJA has wrought. And while world events have overtaken Biden’s young administration’s focus on bringing its version of tax reform to the forefront, I believe it might be prudent to use this lull in Congressional and Presidential focus on the Tax Code to reacquaint ourselves with the key provision of the TCJA and how they impact individual and business taxpayers.

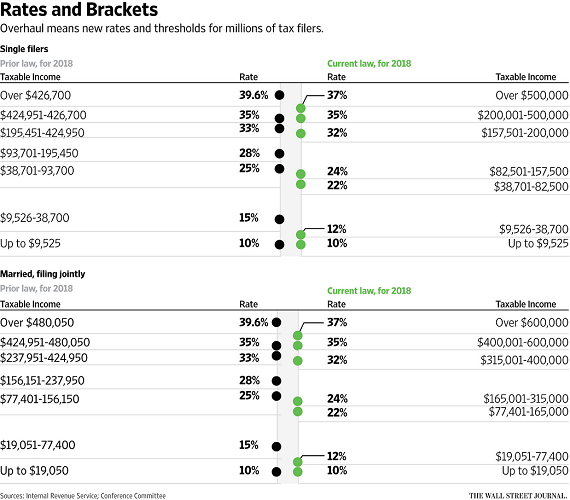

B. Changed Tax Rates and Brackets due to the TCJA of 2017

What follows is a chart comparing the tax rates and brackets for pre-TCJA-2018 and post-TCJA-2019 tax years.

Under the TCJA, the top tax rate drops from 39.6% to 37%, and it takes effect at $600,000 of taxable income for married couples rather than about $480,000 under the pre-TCJA regime. For single filers, the top rate takes effect at $500,000 rather than $426,700. The lowest rate remains 10%, which takes effect at the first dollar of taxable income. However, taxpayers may have more or less income before the 10% rate applies than they did in the past, due to changes to deductions, exemptions, and other provisions.

Let’s quantify the changes for a “typical” hypothetical taxpayer, Mary Jane:

In 2018 when filing her taxes for 2017, Mary Jane, a single lawyer-taxpayer with a taxable income of $100,000 paid $20,842.75 in taxes: ($9,525 x 0.10 = $952.50) + ($29,175 x 0.15 = $4,376.25) + ($55,000 x 0.25 = $13,750.00) + ($6,300 x 0.28 = $1,764.00).

However, in 2019 when filing her taxes for 2018, as a result of the reduction of the tax rates and the expansion of the tax brackets, when filing for the 2018 tax year, Mary Jane, still single with a taxable income of $100,000 paid only $18,289.50 in taxes: ($9,525 x 0.10 = $952.50) + ($29,175 x 0.12 = $3,501.00) + ($43,800 x 0.22 = $9,636.00) + ($17,500 x 0.24 = $4,200.00).

C. Key Deduction/Exemption Changes Bought on by the TCJA

This section highlights the key changes the TCJA of made applicable to individuals. Changes affecting businesses, including provisions affecting corporations versus pass-through entities, such as proprietorships, partnerships, S corporations, and their owners, are addressed in Part E., below.

While the TCJA made a number of important changes to the taxation of individuals, many of these provisions, unless extended by Congress, will sunset in tax years beginning after December 31, 2025 (January 1, 2026), at which time the rules under pre-TCJA law will spring back into effect.

1. Elimination of Taxpayer Personal Exemptions/ Increase in the Standard Deductions

For many taxpayers, especially those with several dependent children, the TCJA’s most sweeping change was the increase in the standard deductions and the repeal of all personal exemptions. The TCJA raised the 2018 standard deduction to $24,000 per married couple and $12,000 for singles, compared with $13,000 and $6,500, respectively, under prior law.

As a result, the number of filers who itemized for 2018 was expected to, and did, drop by more than half—from nearly 47 million to about 19 million out of about 150 million expected tax returns, according to the Tax Policy Center.

As a result of the change, taxpayers can no longer claim a personal exemption deduction for themselves, their spouse or any of their dependents. Each personal exemption in 2017 provided a $4,050 tax deduction. This allowed a family of four to deduct a total of $16,200 in addition to a standard deduction of $13,000, itemized deductions and any adjustments to income. The loss of this personal exemption deduction greatly reduced the tax benefit of the increased standard deduction for taxpayers with large families.

To make up for the loss of this deduction, the child tax credit for qualifying children under the age of 17 was increased by $1,000 and made available to more taxpayers. Additionally, the TCJA created a new $500 credit for all other dependents, though there is no credit for the taxpayer and her spouse.

2. Elimination of Alimony (Paid) Deduction and Alimony Received (Inclusion)

For divorce decrees or separation agreement executed after December 31, 2018, any alimony paid was no longer a deductible expense for the payer. And any alimony received no longer needed to be included in the taxable income of the recipient. It is important to note that this new rule did not affect tax year 2018 returns or anyone who at the time of enactment was then paying or receiving alimony. Taxpayers who divorced before December 31, 2018 continued to be able to deduct and/or are required to report alimony payments as income.

3. Elimination of the Nonmilitary Job-related Moving Expenses Deduction

Under the TCJA, job-related moving expenses paid by an employee lost their deductibility. Only active-duty members of the armed forces who move due to a military order can claim that activity as an adjustment to income. As of the new law, employer-to-employee payments of non-military moving expenses became income that must be included in the employee’s taxable wages, tips, and other compensation reported on a W-2.

4. Limits on Mortgage Interest Deductions for Acquisition Debt and Elimination of the Home Equity Loan Interest Deduction

Under the TCJA taxpayers could continue to claim an itemized deduction for their home mortgage interest on acquisition debt — that is, debt secured by the home and used to buy, build or substantially improve it — up to $750,000 in principal ($375,000 if married and filing separately) on home purchases made after December 15, 2017.

Interest on then-existing acquisition debt of up to $1 million in principal for home purchases made prior to December 16, 2017 was “grandfathered” and remains deductible. The higher $1 million principal limit also applies to acquisition debt incurred before December 16, 2017 that is subsequently refinanced.

Home equity interest – interest on mortgage debt to pay for anything other than to buy, build or substantially improve a residence – became no longer deductible under the TCJA. Additionally, existing home equity debt was not grandfathered.

As a result of the TCJA it has become more important than ever for homeowners who can itemize to keep separate track of acquisition debt and home equity debt going back to the original purchase of their residences.

5. Elimination of the Casualty Loss Deduction

Only a taxpayer who suffers a personal casualty loss from a disaster declared by the president will be able to claim a personal casualty loss as an itemized deduction. Casualty losses are losses sustained by a taxpayer that are not connected with a trade or business or otherwise entered into for profit. They include property losses arising from fire, storm, shipwreck, or other casualty, or from theft.

6. Elimination of the Employee Business Expenses Deduction

Pursuant to the TCJA, none of the previously allowed miscellaneous expenses that were subject to the 2%-of-AGI exclusion remain deductible on Schedule A. Employee business expenses that had not been reimbursed by the taxpayer’s employer were the most prominent deductible items in this category.

Additionally, the TCJA eliminated employee-taxpayers’ ability to deduct business meals, travel and entertainment from their taxes. The eliminated deductions included using a car for business as well as job-related education, job-seeking costs, a qualified home office, union and professional dues and assessments, work clothes and work supplies.

7. Elimination of Investment Expenses Deductions

Investment expense recapture was also eliminated under the TCJA, making it no longer deductible as a miscellaneous expense on Schedule A. The eliminated expenses include custodial and maintenance fees for investment and retirement accounts, fees for collecting dividends and interest, fees paid to investment advisers, the cost of investment media and services, and safe deposit box rental fees. Investment interest remains deductible as interest on Schedule A, subject to the limitations of IRS form 4952.

8. Tax Preparation Fees Deduction

Expenses paid or incurred by an individual in connection with the determination, collection, or refund of any tax are no longer deductible on Schedule A pursuant to the TCJA, no matter which level of government is presiding over the taxation or even what the tax is levied upon.

9. Elimination of Certain Legal Fees Paid on an Award, Judgment or Settlement Deduction

The TCJA also changed the nature and structure of financial agreements between counsel and our clients. For example a legal award, judgment or settlement for personal physical injuries or physical sickness is tax exempt. So, the related legal fees are not deductible since that income is not taxable. Also, in the wake of the “#metoo” and “Time’sUp” movements, there is no deduction for sexual harassment or abuse settlements if the settlement includes a non-disclosure agreement.

Legal fees related to an award, judgment or settlement of claims of unlawful discrimination are deducted as an adjustment to income on the 1040 form, reducing adjusted gross income.

However, all other Legal fees related to all other taxable awards, judgments or settlements, which were previously allowable as miscellaneous expenses on Schedule A, are no longer deductible on the 1040. For example, if a taxpayer is awarded a settlement of $100,000 and her attorney receives $30,000 of it, the taxpayer must pay federal income tax on the entire $100,000 even though she only received $70,000.

10. Doubling of the Estate and Generation Skipping Tax Exemption to $11,400,000 ($22,800,000 for married couples)

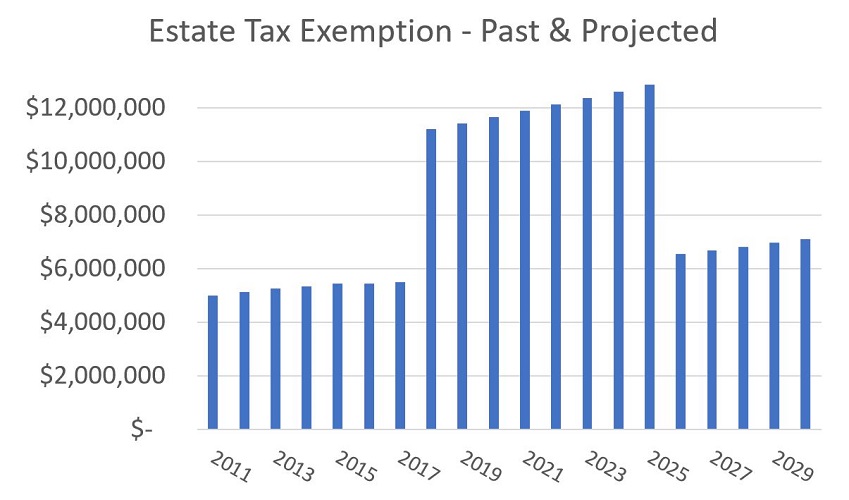

The TCJA doubled the estate and generation-skipping tax exemption to $11,400,000 ($22,800,000 for married couples). Additionally, the step-up in basis is retained at death. As can be seen from the following graph, the enhancement sunsets at December 31, 2025.

Illustration by: Keebler Tax & Wealth Education, Inc.

11. New Flexibility in Education Provisions

Post TCJA, Section 529 Plans allow the distributions of up to $10,000 for “qualified expenses” for elementary school and high school, and starting in 2018, the forgiveness of student loan debt will not be taxable income to the student on account of the student’s death or total disability.

12. New Flexibility for ABLE Accounts

The TCJA also allows for increases in contribution limits in certain circumstances and allows for rollovers from 529 accounts to ABLE accounts.

D. State and Local Tax (“SALT”) Issues

“The U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in South Dakota v. Wayfair Inc., No. 17-494 (U.S. 6/21/18), coupled with the passage of the TCJA, has had the greatest impact on SALT practice in decades, positioning SALT issues to be a one of the leading consideration in the overall tax landscape in the 2019 tax return preparation season and beyond While the reverberation of tax legislation can sometimes take months or longer to take hold, Wayfair and the TCJA began to make waves across the country in just a matter of weeks. For taxpayers and tax professionals this consequence continues to mean that SALT’s influence is now greater than ever, drawing more attention to the key role indirect taxes play in a taxpayer’s comprehensive tax strategy.” [1]

1. The TCJA’s SALT Deduction Limitations

Under TCJA, the SALT deduction was limited to only $10,000.00 per household as to an individual or married filing jointly taxpayer. This limitation has proven to be a handicap for many taxpayers, especially those who are homeowners in high home value states such as California and New York; taxpayers who have traditionally been able to take substantial itemized deductions for both the interest paid on their mortgages and the property taxes paid to their county tax collectors.

However, state, local, and foreign property taxes and state and local sales taxes continued to be allowed as a deduction when paid or accrued in carrying on a trade or business, or an activity described in section 212 (relating to expenses for the production of income).

2. The Impact of Wayfair on the taxation of e-commerce taxpayers.

Wayfair, which held that states can mandate that out-of-state retailers collect sales taxes from in-state customers, even if the retailers have no physical presence in the state. As such, “Wayfair overturned 26 years of precedent (see Quill Corp. v. North Dakota, 504 U.S. 298 (1992)) by changing the nexus landscape from a physical presence to more of an economic influence considering how companies do business in today’s digital climate. Over the past two decades it had been challenging for states to meet budget requirements, and some would assert that this problem was attributed to out-of-state retailers being able to skirt their sales tax responsibilities thanks to the precedent from Quill, which was decided in a less digital world.

“Once the opinion was handed down in Wayfair, it did not take long for states to act and enforce sales tax requirements on out-of-state sellers selling goods and services into their jurisdictions. Before this landmark decision, just 20 states had some sort of economic nexus standard on the books or in the works. Within eight weeks after it, that number was up to 30 plus. The case has also opened the door for states without a sales tax to reconsider implementing one, as e-commerce becomes the norm.

“On the taxpayer side, misconceptions exist that because remote sellers were not charging sales tax on their goods, those transactions were tax-exempt. In reality, those transactions were supposed to be reported on use tax returns, but very few consumers complied with these obligations. Going forward, individuals will likely have to start paying sales tax on more of their out-of-state purchases, which can be seen as leveling the playing field between e-commerce and brick-and-mortar retailers.”[2]

[1] Brawdy, Why SALT will take center stage next to tax reform in 2019, The Tax Adviser (Dec 1, 2018)

[2] Id.

E. Overview of the TCJA’s Reduction of the Top Corporate Tax Rate from 35% to a Flat 21% Rate and Section 199A, the New 20-percent Deduction for Pass-through Businesses Pursuant to Section 199A of the Internal Revenue Code

1. Corporate and Small Business Tax Rates Reduction

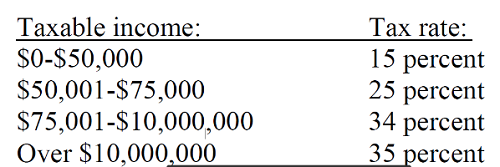

Under the pre-TCJA law, “the highest corporate income tax rate was 35% and the highest rate of tax on qualified dividends received by an individual was 23.8 percent (20% plus the 3.8% tax on net investment income). As a result, under pre-TCJA law, the overall effective rate on corporate income distributed to individual shareholders was 50.47 (35% taxable income plus 15.47% (65% of taxable income times 23.8%)).” [1]

The TCJA eliminated the graduated income tax with a top rate of 35% and replace it with a flat 21% corporate income tax rate beginning in the 2018 tax year.

Corporate Tax Rate

2017

2018

21% Flat rate

According to a joint analysis from the Congressional Budget Office (“CBO”) and the Joint Committee on Taxation (“JCT”), the reduction will reduce revenue by $1.65 trillion over a decade. These corporate tax changes are permanent, while many of the major individual provisions, including changes for pass-through businesses, discussed below, will sunset for tax years beginning after December 31, 2025.

“Also, prior to the TCJA, sole proprietorships and owners of pass-through entities were subject to a maximum marginal rate of 43.4%, (39.6% plus 3.8% if the income was not subject to self-employment (“SE”) tax). Beginning on January 1, 2018, and ending on December 31, 2015, the highest individual rate is now 37% resulting in an effective rate of 40.8% when the net investment income tax applies.

“With the corporate income tax rate now a flat 21% and the corporate alternate minimum tax (“AMT”) repealed, a C corporation distributing all of its after tax profits as dividends to individual shareholders in the highest tax bracket results in a maximum effective rate of 39.8%, (21% of taxable income, plus 79% of taxable income times 23.8%). Thus, the reduction in corporate and individual tax rates after December 31, 2017 reduces the highest marginal effective rate on business income from 50.47% to 39.8% for a C corporation distributing its after-tax profit and from 43.4% to 40.8% for pass-through entities.”[2]

2. An Overview of the TCJA’s Section 199A’s Qualified Business Income Deduction

After all the math is done, Section 199A of the TCJA .grants an eligible business-owner-taxpayer other than a corporation a deduction equal to 20% of the taxpayer’s qualified business income, subject to deduction phase-outs and limitations phase-ins that are dependent upon the type of business the taxpayer is engaged in.

For example, for business owners with taxable incomes in excess of $207,000 ($415,000 in the case of taxpayers married filing jointly), the 20% deduction is phased-out, such that no deduction is allowed against income earned in a “specified service trade or business,” (“SSTB”).

Specified Service Trade or Business

- Health

- Law

- Accounting

- Actuarial science

- Performing arts

- Consulting

- Athletics

- Financial services

- Brokerage services

- Investing and investment management

- Services in trading

- Services in dealing securities, commodities, and partnership interests

- Any trade or business where the principal asset of such trade or business is the reputation or skill of 1 or more of its employees or owners

On the other hand, at these same income levels, the deduction against income earned in an eligible business, a non-SSTB, is limited to the greater of:

50% of the taxpayer’s share of the W-2 wages with respect to the qualified trade or business, or

- The sum of 25% of the taxpayer’s share of the W-2 wages with respect to the qualified trade or business, plus 2.5% of the taxpayer’s share of the unadjusted basis immediately after acquisition of all qualified property.

- 199A’s Business Classifications, Deductions and Limitations

| Non-Service or Non SSTB Service Business | SSTB Service Business | |

| Taxable income less than $315,000 (MFJ 2018) | 20% deduction | 20% deduction |

| Taxable income greater than $315,000 but less than $415,000 | Limitation phased-in | Deduction phased-out |

| Taxable income greater than $415,000 (MFJ 2018) | Wage/Capital Testing | No deduction |

Illustration by: Keebler Tax & Wealth Education, Inc.

- Once the taxpayer’s 20% deduction is computed and limited, as appropriate, it is added to the second deduction offered under Section 199A; a deduction for 20% of the taxpayer’s qualified REIT dividends and publicly traded partnership (PTP) income for the year. These two deductions are truly separate and distinct. For example, if a taxpayer has a net loss from her pass-through businesses, it does not preclude the taxpayer’s ability to claim a deduction of 20% of REIT dividends and PTP income. Likewise, if a taxpayer’s sum of REIT dividends and PTP income is a loss, it does not reduce the taxpayer’s pass-through deduction.

- After each separate deduction is computed, they are added together and then subjected to an OVERALL limitation, equal to 20% of the excess of:

- The taxpayer’s taxable income for the year (before considering the Section 199A deduction), over

- The sum of net capital gain (as defined in Section 1(h)). This includes qualified dividend income taxed at capital gains rates, as well as any unrecaptured Section 1250 gain taxed at 25% and any collectibles gain taxed at 28%.

The purpose of this overall limitation is to ensure that the 20% deduction is not taken against income that is taxed at preferential rates.

3. Advantages and Disadvantages of Business Entity Selection Before and After the TCJA

In the wake of the TCJA taxpayers and their advisors will need to analyze whether a small closely-held business should operate as a C corporation rather than, as most practitioners advised before the TCJA, a partnership or S corporation or other pass-through entity.

Aside from the change in corporate and individual effective tax rates after the TCJA, there remain the same array of tax factors and other considerations that must be taken into account to determine the optimal tax-efficient choice of entity for a small business.

“Because being a C corporation subjects the taxable income of a business to double taxation, most closely held small businesses have historically chosen to be taxed as either an S corporation or as an LLC. An added advantage of an S corporation is that its shareholders avoid self-employment tax on their distributive share of profits. While LLC members often attempt to avoid SE tax by analogy to being limited partners, courts have universally rejected this position, especially where the owners perform services. [See, e.g., Joseph Radtke, S.C. v. United States, 712 F. Supp. 143 (E.D. Wis.1989) aff’d, 895 F.2d 1196 (7th Cir.1990).]

“With the 21% flat corporate rate is now lower than most individual marginal rates and the QBI deduction reducing the effective tax rate on pass-through entity income, the general conclusion that a pass-through entity is necessarily the most tax-efficient choice of entity needs re-examination. In short, the disparity in tax rates between individuals and corporations must be compared with the impact of the QBI deduction for individuals to re-determine the best after-tax return for small businesspersons.

“If an entity, after taking into account the lower corporate tax rate and the QBI deduction, decides to change its status from C to S corporation or vice versa, there are several additional technical consequences from the decision. First, in converting from a C corporation to an S corporation, any excess of the fair market value of the assets of the C corporation over their bases constitutes a net built-in gain which is subject to corporate-level income tax if within 5 years after the S election the assets are sold or the S corporation is liquidated. §1374.

“Therefore, a fast growing business with a need to reinvest its earnings may choose to operate as a C corporation, converting to an S corporation to distribute current earnings when the need to retain capital declines. However, the S corporation will need to wait 5 years from the effective date of the S election before selling any property whose appreciation is attributable to the period it was a C corporation. Conversely, for any corporation revoking its S election to take advantage of the 21% tax rate, the 2017 tax act has a special provision that allows for a six-year recognition period for any §481 adjustment arising from the revocation. §481(d)(1).

“Specifically, the six-year period applies only to an “eligible terminated S corporation,” defined as any C corporation that was an S corporation immediately before enactment of the 2017 tax act (December 22, 2017) and revokes its S election within two years after that date. In addition, the owners of the corporation at the time of revocation must be the same persons who owned the corporation in the same proportions as on the date of enactment of the 2017 tax act. §481(d)(2). In addition, a corporation revoking its S election may extend its post-termination transition period so that distributions by the C corporation are treated as nontaxable amounts from the S corporation’s accumulated adjustment account (AAA) rather than taxable dividends from earning and profits (E&P). §1371(f).”[3]

[1] Williamson and Harr, Being an S or C Corporation for Small Businesses After the 2017 Tax Act and the QBI Deduction, Tax Management Memorandum (BNA) (Feb. 4, 2019)

[2] Id.

[3] Williamson and Harr, Being an S or C Corporation for Small Businesses After the 2017 Tax Act and the QBI Deduction, Tax Management Memorandum (BNA) (Feb. 4, 2019)